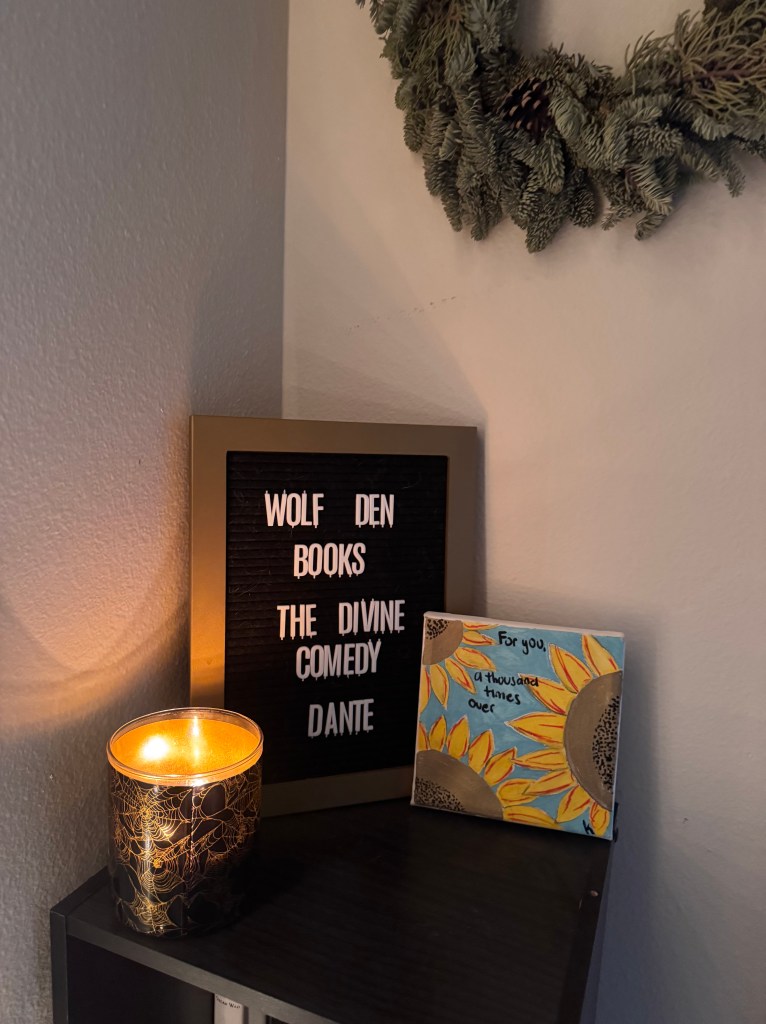

Big news for Wolf Den Books, today–I’ve finished The Divine Comedy.

Hold your applause. The Comedy sat on my shelves for sometime between 5-7 years. And each year that passed, I though to myself, “this will be the year that I read it.” And, of course, it never was the year. I’d be consumed by the thought that I simply was not mature enough to tackle something like this. This is a tough position to be in. As I relay in On How to Read, we have to just keep reading and then read again and again and again. To believe that you need some level of authority or guidance to read something is to create a barrier between you and literature. I personally believe that barriers between the reader and literature should not be present in this way. Ironic, coming from the woman who took years to read this.

Perhaps that makes me a credible source when I say, just read the book. Seriously. I can confidently say that I do not know enough about medieval Europe or the Renaissance to grasp Dante’s reasoning behind name dropping what feels like every influential person in Italy. But, there are people who I did recognize. There was reasoning, philosophy, and ideas that I recognized which ultimately helped push me through to a good enough understanding of his capital-P-Purpose.

What’s more is the ability to take a step back and appreciate Dante himself. Written for the people in the Tuscan language, this helped establish the Italian language that ultimately served as a way for the layperson to take power back from the church. Not to say that The Comedy singularly led the people out of the Dark Ages, but certainly, we can look back and see its pre-eminence in the Italian Renaissance as a whole.

I’ve noted elsewhere that the Renaissance is one of my favorite periods of history. And frankly, the use of the vernacular is one of the reasons why. The choice to write something in a common language rather than a language reserved for the elite gave the people an opportunity to understand in a way that was not available before. Paired with the invention of the Printing Press and you now have a more educated public. This should be the goal, correct?

I read the Rinehart Edition translation with H.R. Huse taking the lead. I am not familiar with other translations, though a quick Google Search leads me to believe that there may be better translations. I am not so sensitive to translations now that I am out of college, but I will say that a good translation makes all the difference. See how even still we rely on the power of language to make literature accessible to us?

Dante’s depiction of the afterlife is fluid and marked by a sense of ascension or progress. Literally climbing out of hell, through purgatory, and eventually to paradise, the reader feels a sense of exhaustion. My senses here lead me to believe that this is the point. That the beautiful, blinding light of Paradise is marked by not just a day’s work, but a lifetime’s work. Compare this to the Medieval use of indulgences and we have yet another way Dante contributes to the people taking power back. That the weight of one’s actions are not singularly defined by one moment, rather it must be the progress made over one’s life.

Perhaps this is just me projecting my own philosophy onto the work, but I also feel Dante’s call to action namely being that there must be a constant sharpening or working of the mind to attain paradise. That virtue lies not only in the “good” acts you did, but also in the way you held fast to knowledge and learning: “Consider what origin you had;/ you were not created to live like brutes,/ but to seek virtue and knowledge” (Inferno, XXVI).

Creation in The Comedy holds weight as it is a Divine Creation that Dante is referring to. That God himself created man to seek virtue and knowledge. This being mentioned in the Inferno leads me to believe that Dante is warning the reader–a call to action. This warning does not go without a source to rectify, though. In fact, I would argue that the entirety of The Comedy is the source of rectification. That quite literally, this work is both the warning and the solution.

I should mention that I am not religious, nor do I feel any particular pressing urge to proselytize paradise onto you, Reader. What I do find convincing and urgent is this idea of seeking virtue through knowledge. It is reminiscent of Aristotle’s eudaimonia which I will, in fact, proselytize at any moment that I get the chance.

I will leave you with this: the concept of paradise is based in the idea of eternal happiness. Dante imagines eternal happiness through an ascension toward God through virtue. Something that is learned and refined over the course of one’s life (or three days if you’re Dante, lucky bastard).

For me, paradise looks different. Eternal happiness is defined at my core through the constant working and re-working of my knowledge. It is found through the existence of learning to which I look upon with veneration. It is the capital-P-Purpose that I cling to at every waking moment. I am nothing without virtue through knowledge. I am nothing without the constant working and re-working of all of the things there is to know. Dante gets it right in the sense that the ultimate goal is the journey feeling just as fulfilling as the end. That, I believe, is what we should strive for.

Leave a comment